What to do when your rope isn’t long enough

This is a follow up article to “Watch your rope – why are people being lowered off the end of their rope”? There we described several things you should be doing to avoid not noticing that your rope is too short, long before the knot in the end comes into play. This you can find in Professional Mountaineer issue 29.

This article will look at what our options might be when you choose to climb a route that you know your rope is not quite long enough for, as well as what to do if you realise, too late, that your rope is not long enough.

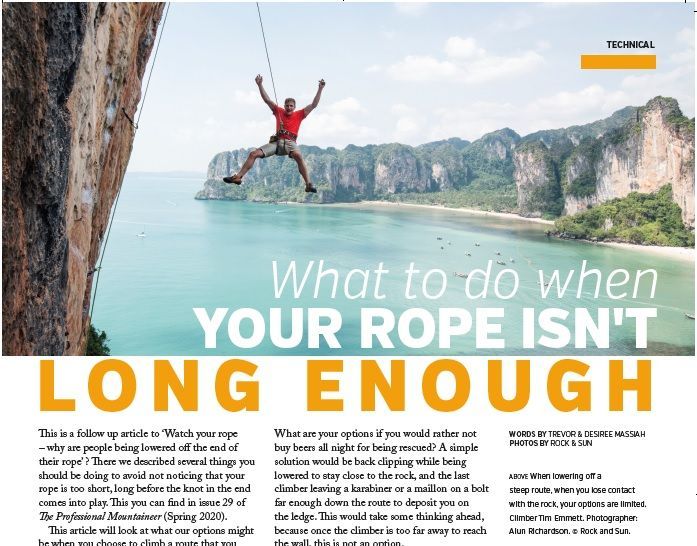

On more than one occasion I’ve had to leave a cold beer over sunset on Tonsai beach and head up to Cat Wall (a steep wall above a narrow ledge 40 to 50m above the beach). A few of the harder pitches are long and if the last party on the crag had a rope only just long enough to reach the ground, but not the 10 or 12m extra necessary to throw and pull the climber back in, they would resort to whistling or shouting for help. A very easy situation to resolve if someone is willing to head up the trail to the ledge with a spare rope to throw and pull the climber back in. It’s an easy mistake but one that wouldn’t happen with a little forward planning for the length and steepness of route verses length of rope.

- A knot in the rope removes the possibility of lowering the climber off the end of the rope but does not solve the problem of not having enough rope to reach the stranded climber. Alternatively, the belayer can be tied into the end of the rope: this also comes in handy for a couple of solutions that we will describe later.

What are your options if you would rather not buy beers all night for being rescued? A simple solution would be back clipping while being lowered to stay close to the rock, and the last climber leaving a biner or a maillon on a bolt far enough down the route to deposit you on the ledge. This would take some thinking ahead, because once the climber is too far away to reach the wall, this is not an option.

The most obvious thing to do to prevent situations like these is to choose routes that are short enough for the rope you have. But, if you’re set on climbing even though your rope is too short (your rope may also have been damaged limiting your options), bear these things in mind:

- When threading anchors: tie back into the end of your rope to maximise length. Threading with a bight of rope can easily use 2m of rope. If you prefer the extra security of threading a bight of rope through the anchors and being attached to the rope before untying, then do so. But when you would normally be done, tie back into the end and then remove the bight.

- When climbing steeply overhanging routes from a ledge as opposed to from the ground it is fairly standard to back clip (unclip the belayer’s side of the rope and clip your rope in) to ensure you lower back to the ledge rather than hanging out in space. Another solution would be for the belayer to toss the end of the rope to the lowering climber and pull them back into the belay ledge.

When your rope is too short for these suggestions to work, there are at least 5 solutions.

Solution 1 – Thread another anchor

- Check for mid-point double bolt lower offs. These are often in place for routes of 40m or longer (sometimes 35m+ routes). While being lowered off the top anchor, stop at the mid-point anchor, clip in direct, and rethread the rope through this lower anchor to make it to the ground.

- Essentially the same: Check for shorter routes nearby that you can swing across to and use as an intermediate anchor.

Solution 2 – Maillon(s) or leaver biner(s)

When there is no lower anchor to use, consider using a ‘leaver biner’ or maillon on a bolt lower down. Do consider the quality of the rock and condition of the bolt. Leaving gear on two consecutive bolts is an option if concerned. Please do not overtighten maillons, so they can be removed by a subsequent party – in some circumstances they can create leverage on the karabiner when clipping in front rather than behind the maillon. I’ve seen at least one karabiner failure due to this.

Solution 3 – Prusik up the rope

When you can’t make it to the ground and have lost contact with the wall, prusiking up the rope to a point where you can contact the rock is of course an option – although not many sport climbers carry prusik loops with them on single pitch routes.

I once witnessed Crispin Waddy (one of the UK’s most accomplished adventure trad climbers) abseiling, until reached the end of his rope 20m from the ground. A very angry and concerned Heinz Zac (the famous Austrian climbing photographer) raced up a route to throw a rope to a very bemused Crispin who was already happily prusiking up his abseil rope using his shoe laces! Luckily, he wasn’t wearing Velcros. Of course, Crispin accepted the rope. I’m certain neither knew who the other was which amused me no end.

Solution 4 – Belayer climbs up to lower climber

When you know beforehand or realise while lowering that your rope is not quite long enough, this solution can work on routes that are not overhanging, if the belayer intends to follow the pitch after lowering the leader. The belayer ties into the end of the rope – preferably beforehand but it can also be achieved after locking off the belay device. Once the climber and belayer are counterbalanced, the belayer starts climbing – thereby lowering the other climber to the ground. If necessary, the belay device can be removed once there is enough slack in the system; the climber may need to clip in direct to a bolt to do this. It is not necessary to do this if you have more than one belay device. The previous climber can simply put the new climber on belay when there is enough slack. Up to this point the climber is protected by the person on the ground staying tied in. I’ve used this solution on many occasions, and it is often possible to judge that once the draws are cleaned from the pitch and the rope is running in a straight line, the climber will make it back to the ground on rope stretch – therefore this technique is less effective if the rope is more than a few metres under-length.

Solution 5 – a spare rope (or slings)

What to do when none of the above solutions work, i.e. the climber is hanging in space so can not get to an intermediate anchor, nor re-thread a bolt by leaving a maillon, nor can he/she prusik up the rope?

I’ve used this on a couple of occasions when strangers at the crag have found themselves up to 5m plus off the ground and with a belayer who is unable to climb the route. The belayer steps backwards to retain the last metre or so and locks the belay device; the spare rope is attached to the end of the belay rope, and a belay device (or Italian Hitch) is fixed. Then, place a releasable prusik on the rope above the belay device and weight it to remove the belay device and transfer the tension to the added rope. The prusik can now be released and the climber lowered further – however, only until the knot hits the first runner – the limiting factor for this method. Alternatively, on occasion I’ve attached four 120cm slings and one 240cm linked together to the end of the rope, effectively lengthening the rope. The belayer clips into the end sling and the one closest to the rope. Once the prusik is removed the climber can be lowered using the belayer’s body as a counterweight, and unclipping from 1st to 2nd to the 3rd sling, until reaching the final sling and walking forwards until the climber is back on the ground. This is one to practice somewhere safe before trying in anger!

Summary: Preparation – Awareness – Carry

- Preparation; how long is rope, how long is route, how steep is it? Knot both ends of the rope as standard practice.

- Awareness; Keep an eye on the end of the rope. Look out for mid anchors, or lower stations on adjacent routes. When lowering off steep routes, stay in touch with the wall.

- Carry maillons or leaver biners, slings and prusiks and know how to use them.

- Last resort: call for help and buy the first round.

Words by: Trevor (MCI) and Desiree (RCI) Massiah are the Directors of Rock & Sun, who offer climbing courses and holidays in the UK, Spain, France, Greece, Italy, Morocco and Thailand, and bouldering trips to Fontainebleau

and Albarracin. Rock & Sun provide high quality coaching courses for all levels.

Photos by: Alun Richardson and Rock & Sun