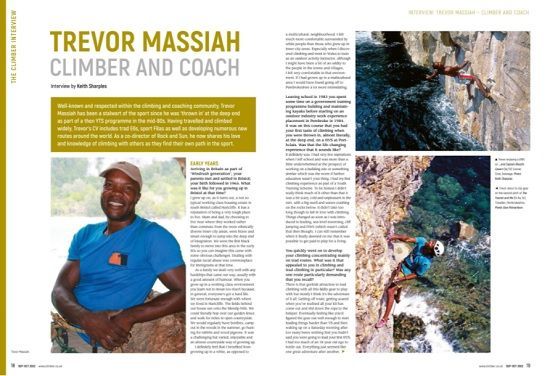

Trevor Massiah: Climber and Coach

Published in Climber. Edition: Sept/Oct 2022, p.18. https://climber.co.uk

Trevor Massiah: Climber and Coach

Interview by Keith Sharples

Well-known and respected within the climbing and coaching community, Trevor Massiah has been a stalwart of the sport since he was ‘thrown in’ at the deep end as part of a then YTS programme in the mid-80s. Having travelled and climbed widely, Trevor’s CV includes trad E6s, sport F8as as well as developing numerous new routes around the world. As a co-director of Rock & Sun, he now shares his love and knowledge of climbing with others as they find their own path in the sport.

Early Years

Arriving in Britain as part of ‘Windrush generation’, your parents met and settled in Bristol; your birth followed in 1965. What was it like for you growing up in Bristol at that time?

I grew up on, as it turns out, a not so typical working class housing estate in south Bristol called Hartcliffe. It has a reputation of being a very tough place to live. Mum and dad, by choosing to live near where they worked rather than commute from the more ethnically diverse inner-city areas, were brave and smart enough to jump into the deep end of integration. We were the first black family to move into this area in the early 60’s so you can imagine this came with some obvious challenges. Dealing with regular racial abuse was commonplace for immigrants at that time.

As a family we dealt very well with any hardship that come our way. Usually with a good amount of humour. When you grow up in a working-class environment you learn not to moan too much. Because in general everyone’s got a hard life.

We were fortunate enough with where we lived in Hartcliffe. The fields behind our house ran onto the Mendip hills. We could literally hop over our garden fence and walk for miles in open countryside. We would regularly have bonfires, camp out in the woods in the summer, go hunting for rabbits and wood pigeons. It was a challenging but varied, enjoyable and almost countryside way of growing up.

I definitely feel that I benefited from growing up in a white as opposed to a multicultural neighbourhood. I felt much more comfortable surrounded by white people than those who grew up in inner-city areas. Especially when I discovered climbing and went to Wales to train as an outdoor activity instructor, although I might have been a bit of an oddity to the people in the towns and villages, I felt very comfortable in that environment. If I had grown up in a multicultural area I would have found going off to Pembrokeshire a lot more intimidating.

Leaving school in 1983 you spent some time on a Government training programme building and maintaining kayaks before starting on an outdoor industry work experience placement in Pembroke in 1984. It was on this course that you had your first taste of climbing when you were thrown in, almost literally, at the deep-end on a HVS at Porthclais. Was that the life-changing experience that it sounds like?

It definitely was. I had very few aspirations when I left school and was more than a little underwhelmed at the prospect of working on a building site or something similar which was the norm if further education wasn’t your thing. At the start of this YTS in Pembroke I had my first climbing experience. To be honest I didn’t really think much of it other than that it was a bit scary, cold and unpleasant in the rain, with a big swell and waves crashing on the rocks below. It didn’t take too long though to fall in love with climbing. Things changed as soon as I was introduced to leading, sea-level traversing, cliff jumping and DWS (which wasn’t called that then though). I can still remember when it finally dawned on me that it was possible to get paid to play for a living.

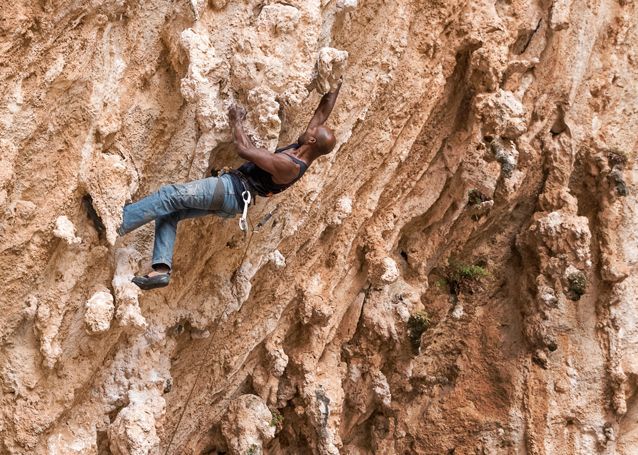

You quickly went on to develop your climbing concentrating mainly on trad routes. What was it that appealed to you in climbing and trad climbing in particular? Was any one route particularly demanding that you recall?

There is that geekish attraction to trad climbing with all this fiddly gear to play with, but mostly I think it’s the adventure of it all. Getting off route, getting scared when you’ve realised all your kit has come out and slid down the rope to the belayer. Eventually feeling like you’d figured the gear out well enough to start leading things harder than VS, and then waking up on a Saturday morning after too many beers wishing that you hadn’t said you were going to lead your first HVS. I had too much of an 18-year-old ego to bottle out. Everything just seemed like one great adventure after another.

Probably the most memorable routes for me is: The land that time forgot. It’s in range West on a crag called Mount Zion Central. It’s a 200m 5 pitch route that I did with Ian Parnell in ’98. We thought it deserved E6 at the time but I think the grade may have settled down to E5 6a. It’s a traverse along an obvious central break below an impending steep wall above. It starts up an E3 (Red Zawn) then continues with 4 long pitches traversing the crag in it’s entirety. The route was, as usual, attempted ground up swinging leads. I randomly got what turned out to be the crux pitch. This pitch, as did a few others, involved cleaning out a horizontal crack of a damp clayish red mud as you climbed. On the crux section of pitch 4, where the break thinned to around first joint tips, the crack would remain damp after cleaning enough space for gear and fingers with a nut tool. On the first attempt I fell, ripped a small wire and took a huge maybe 40ft or more pendulum fall onto a small blue Alien. The crag is so steep at this point that there’s no chance at all of avoiding a lower into the sea. As it was getting close to sunset I asked Ian to lower me to sea level where, much to the amusement of several other parties, I attempt to paddle with my hands just above sea level trying to create enough swing to avoid getting completely wet, that predictably failed and the swim was taken. We returned the next day and jugged up the ropes to the start of the pitch, the cracks were still damp and I fell again but this time prusiked back up and climbed through. Those few years climbing and exploring with friends on the Pembrokeshire cliffs were definitely some of the best climbing experiences I’ve ever had.

Travelling, New-Routing and the Great Outdoors

Pretty soon you started traveling widely climbing in numerous countries including Australia, South East Asia, China, New Zealand and the US. What are your stand-out memories from that time?

In ‘92 I bought a round the world ticket and headed off with a backpack for a big adventure. It was amazing to fly into Delhi and experience being in Asia for the first time. I hooked up with a bunch of local Indian climbers and got taken out to some of the new places being developed in India like Bangalore and Hampi.

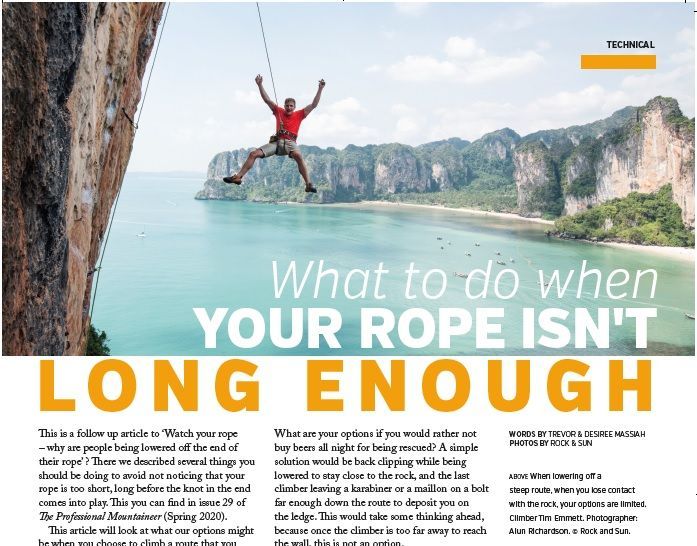

Thailand also stands out of course. I travelled through Thailand on my way to Australia and had unfortunately left my climbing gear in Malaysia – which I immediately regretted. I was very impressed with the beautiful multi-coloured limestone crags with stalactite systems hanging off them. And with the karsts, the weird limestone lumps of rock sticking out of the sea. After spending close to a year in Australia I therefore decided to head back to Thailand. This time wíth climbing gear ánd with more experience. Because during my time in Australia one of the top South/Western Australian climbers (Shane Richardson) had introduced me to the idea of putting up sport routes. We teamed up and did a lot of new routing in Western Australia. After that experience I was pretty sold on the idea of going back to Thailand to get involved with developing sport routes there. I have been back to Thailand almost every winter since then, to climb, to run climbing holidays with Rock & Sun, and to develop new routes and climbing areas.

What, if any, variances did you see in climbing and the sport ethos across the places you visited at that time?

In Australia it was the first time I came across trad and sport routes coexisting next to each other, and routes that were a mix of sport and trad. You could be climbing trad and if there was a runout there could be a carrot bolt and then it might be trad again. It would otherwise be an E6 or E7, excluding the masses from being able to climb. That mix of sport and trad seemed to work really well in Australia.

Up until this summer, rebolting on the Orm, I had never actually placed a bolt in the UK. I have only ever put sport routes up in other countries. The trad climbing in the UK is so amazing that when I am in the UK I just want to go trad climbing.

Another observation is that redpointing wasn’t a thing. I hadn’t redpointed a route until I started bolting routes in the early 90s. When I would go sport climbing, in the Verdon or the Costa Blanca, I may fall off a move and try again, but certainly wouldn’t do repeated attempts until I could do it clean. But when I started developing sport routes it meant that I then actually had to climb them. Because when you put the bolts in you don’t want to walk away not having climbed the route. So that led me into redpointing.

Where was your favourite place to climb and why and is that still the case today?

My favourite place without a doubt would still be trad climbing in the UK. The Pembrokeshire sea cliffs are definitely one of my all time favourite places to climb. My Top other destinations would be Thailand, El Cap/Yosemite, Taipan Wall, and the Needles in California.

Along the way you got hooked on developing new routes on your travels – something which you still do to this day. Of the hundreds of new routes you’ve developed are there some which were particularly memorable and if so why?

Humanality is a 6 pitch route in Thailand, above Ton Sai beach. It’s not particular hard, but the whole experience of putting it up with Greg Collum, over a period of 10 days or so was incredible. I think it may have been my first multipitch trad lead in Thailand. Starting on the beach, zigzagging through these massive tufa/stalactite systems, we got all the way to the top of the route without placing a single bolt. Back then it was hard to know how the tufa would hold up to nuts and cams as tufas tend to be so much softer than actual rock. We placed as many slings/threads as possible and placed jammed knots if the rock felt or looked particularly soft. The route turned out to be a mega classic. One of the most popular multipitch routes in Thailand. The 5th pitch goes up a gradually steepening wall on good holds until it blanks out completely. Exactly at this point there’s this huge stalactite at shoulder level behind you, you look across thinking maybe it’s possible to lean across and reach it. It takes a little bit of convincing but it goes. You transfer onto it, do a few meters of climbing on the tufa then step back onto the wall where the holds reappear.

I really enjoy the whole process of finding a crag or line getting to the top ideally via a trad lead then creating a fun sport route. The grade is not important to me at all. It’s definitely about the process and creating something that’s fun and safe to climb.

Coaching, Health and Safety Advisor and TV Work

You’ve worked in the outdoor industry since the 1980’s; much of that time as a full member of the Association of Mountaineering Instructors. What are the main changes have you seen whilst working in the industry?

The standard of instruction and especially coaching has come a long way since then. Mountain training and AMI have done amazing work to put an award system in place, achieving high quality and consistent instruction. Running Rock & Sun we travel a lot around Europe and further afield and recognise that in general the quality of British instructors is so much higher.

In 2012 you met Desirée Verbeek whilst climbing in Thailand; then, in 2013, you joined Rock and Sun – a company which specialises in delivering rock climbing holidays and coaching for outdoor climbing – as a director. Desirée, joined as a director the year after. How satisfying do you find it working alongside your partner whilst running your own business and introducing others to climbing?

We feel it is a real privilege to make a living out of living your dream and having the freedom to design things the way we want them to be. Running Rock and Sun allows us to travel and climb all over Europe but also Africa and south East Asia. We are very lucky that we can work together so well at the crag as well as in the office, and then also enjoy climbing together when we’re not working. We simply love what we do – probably because we designed it the way we wanted it to be.

Do you find coaching others has impacted your own climbing at all? Do you, for example, apply some of the development techniques you show to others to your own climbing?

Coaching has definitely impacted my own climbing in a positive way. I regularly say when I am coaching that my technique was pretty rubbish before I started coaching but I was a lot stronger. Coaching allows you to identify inefficiencies in others people’s climbing and come up with ways of practicing climbing in a way that creates a more efficient movement pattern. It’s almost impossible then not to apply the same approach to your own climbing.

Black Lives Matter

Following the conviction for George Floyd’s murder and the continuing growth of the Black Lives Matter Movement you’ve joined the debate talking about your experience as a person of colour. You’re on-the-record as saying “Racism within climbing isn’t something I’ve experienced”. That is a great endorsement for the sport – right?

It’s true that climbing is not particularly ethnically diverse. Of course this is something that is changing quickly and has been doing so from the early 90’s when climbing walls began to spring up in the major cities around the country. Having climbed and travelled a huge amount during the past four decades I have never directly experienced any racism within or from anyone within the climbing community. I’m not saying that there aren’t racist climbers, racism exists in all walks of life and in all communities but in my experience the climbing community stands out as being an open minded, and welcoming community full of odd, weird and wonderful characters.

Most climbers are open-minded; do you think that is fuelling the increase in diversity in the climbing community which is evident today?

Through our work with Rock & Sun we notice that a lot of people only really went into the gym to climb because they thought it was just more fun than going to the mainstream gym, pushing weights, rowing machine or running on the tread mill. As more climbing/bouldering facilities are built in inner-city areas it is naturally going to attract a greater diversity of individuals.

Is there anything else you would like to add to the conversation about equality and representation within the sport?

Future

Is there anything specific within the sport and or coaching you still want to achieve?

I very much feel that I’m improving as a coach year by year. Both Dees and I enjoy figuring out new ways to explain, teach and practice techniques. We also hope to create more time for our own climbing which the pandemic has made incredibly challenging. I have so far managed to improve my climbing grade in each decade and still have 3 or 4 years to try and climb harder in my 50s than I climbed in my 40s. Climbing harder in my 60’s may be more of a challenge but I do enjoy setting myself random targets as a way of motivating myself.