Climbing Skill Sets

Performance in climbing is a combination of three main skill sets. It is necessary to have these three aspects functioning optimally for your performance on the rock to be close to or at your maximum capability. Having these skill sets closely aligned will ultimately bring greater enjoyment and satisfaction to your climbing experience.

There is technique, understanding how to move efficiently on vertical ground. There is the mind, the ability to calm the mind down when it feels under pressure, the ability to deal with the natural fear of being off the ground. And then a climber’s physique, strength, power-to-weight ratio, and stamina (see Figure 1).

All three are coming together while climbing. You can’t just rely on your physique, power and stamina, nor just on having amazing technique, or on having a very strong mind. What we notice when we are coaching is that the climber’s performance can not exceed the level of the least developed skill. Let’s illustrate this.

Climber A has quite good technique, has got footwork and knows how to climb using as little upper body power as possible. When on lead, Climber A however finds they are often too scared to move above a bolt, to then fly up the same route when on a toprope; obviously not held back by the technical ability to climb the route. Climber A’s strength and fitness levels are high enough to climb harder. What is holding this climber back is a lack of skills to deal with mental challenges related to climbing. Getting fitter and stronger may make this climber feel more confident in being able to hold on to the holds, and it would buy time to figure out a technical solution for the crux, but ultimately this climber would benefit from exercises to train her mind.

Climber B on the other hand is a strong and physically gifted climber who is not so much distracted by fears. But with poor technique this climber is wasting a lot of energy, and therefore not climbing to their full potential. Mainly pulling on the holds and regularly dragging a leg behind on the easier part of the climb, means the climber is pumped when arriving at the crux of the route. Not held back by fear, Climber B slaps for the hold, makes it, but has no strength left to hold it and falls.

Climber C is a very experienced climber with close-to-being-perfect technique. With over 30 years of climbing experience, mainly trad, this climber has developed very good route-finding skills and is prepared to fall off on both trad and sport routes. Going out climbing regularly means Climber C has a good base level of fitness. But because they never trained specifically for climbing, physical abilities hold back their performance before anything else.

Importance of the basics

Before we continue, there is obviously one more aspect to climbing: the basics. Getting the basics right is most important, and superseding all else. We regard the ability to assess risks, the skills to keep oneself (and your belayer) safe, and route-finding as the basics of climbing. You can be as strong, technically proficient or brave as you like, but if you can’t do a correct risk assessment, and/or don’t know how to keep yourself safe, and/or lack route-finding skills, you may get yourself into trouble.

People who lack the ability to keep themselves safe are the last people you would want to make more confident. They might get so casual with exposing themselves to unnecessary or serious risks that they could hurt themselves – or others. What they need first is to become safe climbers. At Rock & Sun we therefore pay a great deal of attention to safety. Initially we focus on clipping technique and positions, belaying, rope awareness, threading anchors, and risk assessments. There are many ways of doing these things and the important thing – especially for experienced climbers – is to keep your ears and eyes open for new developments and improved ways of doing the things you may have done a certain (possibly suboptimal) way for years or even decades. On the Rock & Sun YouTube channel we published several instructional/safety videos[i]. We also spend a great deal of attention to route finding skills – asking the question: “where is it less steep and more featured, from the feet up?” – practicing this for instance with a laser pen exercise[ii].

Once these basic principles are established, climbers can choose to train to get fitter and stronger, or to train the climbing brain, or to improve their climbing technique, or attempt to do it all.

Why we focus primarily on technique and efficient movement

We work closely with hundreds of climbers each year, we analyse their climbing, and dare to say that 90% of them are held back by their climbing technique. Some may think they are being held back by strength and fitness. Others may think that a fear of falling is holding them back. When we’re analysing climbers’ movement patterns, the reality is though that it is mostly people’s lack of understanding the biomechanics and how that affects efficient movement that is holding them back. This is compounded by a lack of route-finding skills. This is no surprise, as most climbers learn to climb in an indoor environment; they have limited time and opportunity to go outside and climb on rock. Climbing indoors, where routes are designed to get harder by putting the holds further apart and forcing the climber to use less than efficient movement patterns, means that when climbers come to climb outdoors they apply their ingrained (indoor) movement patterns on the rock, not recognising that easier options than the moves they choose are available. We will not go into too much detail here, but refer to our previously written articles on Outdoor Climbing Coaching, our video Inefficient vs Efficient Climbing, and to an example of our Video Analysis.

Fear starts in the forearms: Mind – Technique axis

Technique and the Mind are two linked skill-sets (see figure 1). Let’s illustrate this: When climbers lack technique, and lack understanding of where to look for footholds and how to execute moves, they will inevitably overuse their upper body. They will rely more on their arms for their upward movement than is strictly necessary. As a consequence, they are getting pumped quicker, and thát is the moment that the fear sets in: fear usually starts in the forearms. Plus, balancing on the rock face with only one foot is much more scary than moving up on both feet. Climbers rarely show fear when climbing above a bolt when they are on a route that is well within their grade – even though the consequence of falling might be more severe. So it is not necessarily their mind that is holding them back when climbing away from the protection. The mind usually becomes fearful when the climber is facing the prospect of falling, knowing they can’t hold on for much longer.

These climbers could choose to improve their climbing potential by working on their mental skills, but the root of the problem is their lack of understanding of how to move on vertical ground. Once they understand that – and are disciplined enough to reprogram their movement, they are saving upper body strength and it will take much longer before they get pumped – and scared. We reckon that most people we work with have at least two grades of climbing improvement in them, based only on improving their basic movement pattern.

Technique is an easy fix

A nice bonus of acknowledging that it is a lack of technique that is holding you back, is that it is relatively easy to fix. It is not rocket science; it is simple body mechanics. Once you understand the physics, and once you have received personal coaching to understand which bad habits you need to rewire, and have a set of drills that work for you to reduce your weaknesses, all it needs is discipline. As opposed to trying to improve your climbing by getting fitter to postpone the pump. How many people got into climbing because they love doing pull ups, push ups, and deadhangs?! Based on the climbers we work with on our courses and holidays (and on people we watch climbing while at the crag) we are convinced that most climbers do not need to do any additional physical training until they want to climb higher 7s.

Another good reason to focus on developing your movement skills instead of getting fitter and stronger, is that strength and fitness are easily lost during a period of not training or not climbing. After being ill or injured, pregnant, or a too busy period in your life where you did not have time to go climbing, your level of fitness and strength can be greatly reduced. Your technique however stays!

Fear is related to basic skill of doing risk assessments

Having described the link between technique and the mind, we now move on to explaining how someone’s ability to deal with a fear of falling is also strongly related to the basic required skill set of being able to do an accurate risk assessment. If physics isn’t your strong point, when doing your route finding (i.e. trying to find the less steep and most featured way to the next bolt, providing it is safe to go that way) all your options may come back as unsafe. “It is less steep and more featured on the left but if I go that way and fall off, I will swing into that feature there. The route definitely doesn’t go right here, because that’s looking too hard for the grade. I could go straight up here, where it is steeper and the holds are smaller than on the left. It keeps me closer to the bolt, but if I fall, I will land on the ledge I am leaving.”

It is completely normal (and sometimes even necessary) to be scared, because falling is not a natural thing for human beings to do. If you think you will hit something and hurt yourself, being scared prevents you from taking that risk. We should see fear as our friend. However, not being able to assess the angle, direction and length of the fall correctly, and assessing the risk as higher than it is, means you may be unduly scared.

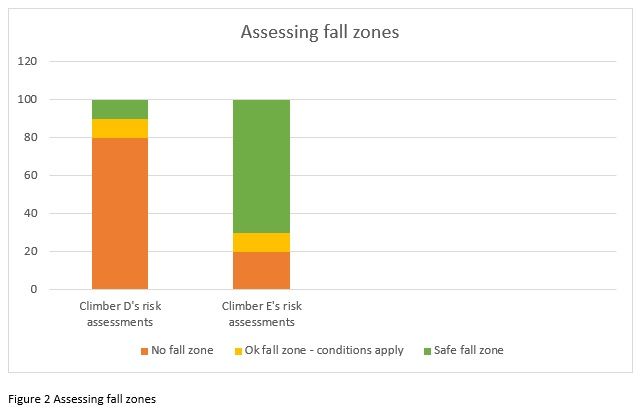

Figure 2 helps to illustrate this. In a hypothetical situation, Climber D and Climber E are climbing the same 100 routes. Climber E always makes correct risk assessments: 20% of falls resulting in sustaining a serious injury, 10% of falls can be managed by f.i. deliberately pushing off while falling, and by an attentive and skilful belayer, and 70% of the falls are safe. Please note that the numbers are hypothetical – it should not be interpreted that if you do a correct risk assessment, 20% of the falls are in a “no fall zone”. Climber D however, on those same 100 routes, thinks that 80% of the time falling off would result in injury, and only 10% of the falls are safe. No surprise that Climber D feels scared.

For Climber D it would be really helpful to make more accurate risk assessments. There are at least three easy ways to do this:

1) while on the ground, get into the habit of watching other climbers climb and imagine their fall if they were to fall off at any point, given the distance from the bolt and the amount of slack in the system. If at some point you assess the fall as not safe, ask a more experienced climber what their assessment of the fall would be.

2) while on the ground, watch other climbers taking falls. Was the fall what you had imagined it to be? This is especially helpful when a climber falls off the crux of a route that you are struggling to commit to. Once you’ve seen someone else fall in the same spot, your risk assessment can be adjusted.

3) while climbing and not willing to commit to a move because you assess it as possibly dangerous, ask your belayer how they assess the fall. Is it safe to commit?

Improving this basic skill set helps to be less scared, helps to calm the mind, and re-focus on the climbing.

Conclusion

To maximise your climbing potential, you need to assess (or ask a professional climbing coach to assess) what your weaknesses are and how these interrelate, in order to get the right exercises for you to improve. Work the weakest link! Work its true source, which may not be the same as how the weakest link manifests itself (remember that ‘fear from the forearm’ is most likely coming from a technical deficiency, not a lack of strength).

Based on several decades of experience with performance coaching for climbing, we conclude that most climbers need, first of all, to be able to make correct risk assessments, to know how to keep themselves safe, and to improve their route-finding, i.e. they need to get the basics right. Then, most room for improvement lies in learning how to move efficiently on vertical ground by understanding biomechanics and applying what we refer to as ‘a basic movement pattern’. As explained before, both of these have a positive effect on the mind. With correct risk assessments of fall zones, there is less reason to be scared. Knowing how to move efficiently saves upper body strength, which means you’re less likely to get pumped – and scared. Development of technique and the mind go hand in hand; by doing lots of mileage climbing easy routes the mind is calm and able to focus on efficient body movement.

When climbers have invested in improving their technique and in their basic risk assessment and route-finding skills, we consider training the brain as the best next choice of action. There are many exercises that help to stay calm and focused on the rock. We have worked together with Hazel Findlay on several occasions; she is a professional climber who specialises in coaching the mental aspects of climbing.

We do of course acknowledge that there is an advantage to being strong and fit. Looking at the Physique – Technique axis, stamina buys you time to figure out the most technical solution to a crux, and strength and power mean you have a greater selection of holds available to you. Furthermore, on the Physique – Mind axis, feeling strong enough to hold the holds, can give an advantage. It can calm the mind and help you to commit to a move. What we notice though is that most of our clients don’t lack strength or fitness.

(written by Desiree Verbeek)

***********************************************************

Interested in a Performance Coaching Course?

Keep an eye on our blog for our next article on Route-finding.

***********************************************************

[i] These videos are not intended to replace face to face instruction by a qualified climbing instructor, they are intended as refreshers for those having been on a Rock & Sun course or holiday.

[ii] Our next article will be about route finding, so keep an eye on our blog. We will accompany it with a video, which will be published on our YouTube Channel.