Navigation for Rock Climbing

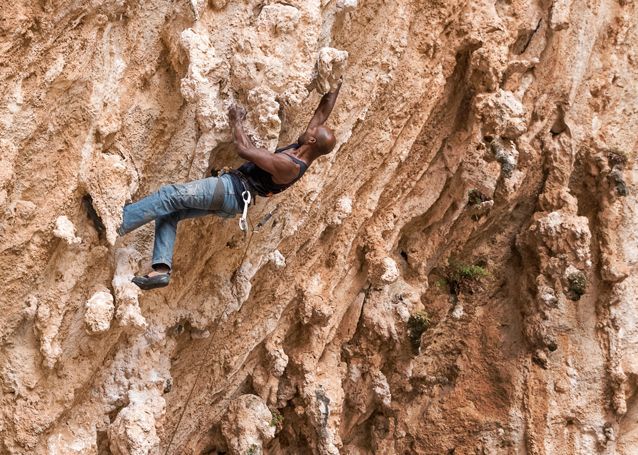

In the previous blog ‘A Climbing Framework for Sport Climbing’ we looked at a framework as an aid to better decision making for leading. The framework included a simple formula for navigating between the bolts:

Navigate only for the feet, choose hand holds based on the direction you want your feet to travel. Go where it is less steep overall for the feet but be sure to risk assess your chosen route before committing to it.

In this blog ‘Navigation for Rock Climbing’ we are going to provide a deeper explanation of the rationale behind it because, although it sounds simple, it’s a bit like learning to use contour lines when map reading. It takes some practice before the information jumps out at you, and you also need to fully understand and trust the process to commit to practising it.

Find -and climb- the easiest way

Apart from safety and coaching efficient movement, route-finding or navigation has become a primary focus when coaching outside. The fundamental concepts of moving more efficiently are usually easily understood as there is immediate feedback of the climbing feeling easier, the upper body having to work less, and the arms not getting as tired. On a Coaching Course, which is 5 climbing days filled with video analysis, theory and drills and exercises to understand and practise efficient movement, climbers improve on average two grades in one week. With navigation, people can take a long time to understand and engage in the process, especially because seeing the change in angles is difficult at first and it requires climbing routes in several different (steeper and less steep) ways to compare and get the evidence. Plus, after the week of climbing outdoors, this skill can not continue to be practised indoors. In our experience more than 90% of the climbers that we work with climb at least 2 grades harder indoors than on rock. People were still way off their true potential despite the obvious improvements in their movement skills. So, we realised we needed to put a greater emphasis on route finding. However well you move on the rock and whatever strength and fitness gains you make, none of it will fully translate to your maximum grade if a good percentage of the time you are navigating the “wrong” (harder) way. It is possible to argue of course that there is no wrong or right way as we have the freedom to choose where or how we climb each route, but when coaching we are being asked to help people climb to their full potential, so this involves both technique and navigation (climbing the route the easiest way and doing the most efficient moves).

Sandbag? Or did you not find the easiest route?

We were fortunate enough to have a lot of spare time on our hands during the pandemic and chose to spend much of it developing our local crags. Our motivation with new routes has been to bolt at a useful grade for coaching on. We noticed quickly that many local and independent climbers thought many of our routes were sandbags (much harder than anticipated). Fortunately, we are often able to watch these routes being climbed while working with our groups. We have been surprised or even shocked at some of the route-finding choices and fully understand why the routes were thought to be under graded. I couldn’t resist trying to climb a 6a+ that we had bolted the way we had seen several climbers try it. Climbed this way I figure it would be at least 7b!

While observing and discussing with our clients how they determine where a route goes, it is apparent that most climbers use things that are not necessarily helpful such as chalk, handholds, the bolts or an arbitrary distance that they are allowed to climb left or right of the bolts. Therefore, we have tried to come up with a dependable way to assist with route-finding choices rather than just beta which is only useful on that one route. We find ourselves constantly repeating the mantra of ‘look at your feet and follow the least steep way to your destination’. This is literally what we always start with when climbing for ourselves and we find it hard to think of routes that do not fit with this approach.

Climbing is problem-solving

Climbing is a problem-solving exercise. The first three parts of the problem are cerebral not physical:

- Reading the rock/navigating. Where does the route go?

- Risk management. Is where I want to go reasonably safe?

- What sequence of holds and movement is most efficient.

Only then do we get to do the physical bit: moving in the chosen direction in the most efficient way.

The other route does not exist

We often hear questions like ‘isn’t that the other route’ or ‘am I allowed to go that way or is that cheating?’. These questions often refer to ‘will I have climbed the grade or made it easier?’. We find this interesting, as routes are graded for the easiest way, and the whole point is to find that easiest way. If there is a safe easy way to do the route, then that solution is the grade.

We’d like to emphasise that while route finding any bolts on other routes can be ignored. When bolted routes are close together, one of the routes was there first so all the holds on that section of rock were part of that route. It does not make sense that when a new route gets bolted that some of those holds are then considered as no longer ‘in’ because they are now ´on the other route´. We often find ourselves saying ´the other route does not exist´ and ´the other bolts do not exist´. You are climbing your route, with your line of bolts there to keep you safe. So you go where it is easiest, least steep and safe for your route. The only route that exists is the one you´re climbing at that moment. Granted, the rock being the surface we climb on, sections of it can be climbed by multiple routes. Multiple routes may use the same section of rock.

Besides the point we´re making that you can´t be ´on the other route´, there is also no such thing as being ´off (your) route´, unless your chosen route is unsafe, in order words: unless the bolt does not keep you safe on your chosen route.

When the hardest routes in the world are climbed the first ascensionist might be searching for the new hardest line, but they are not going to avoid an easier section then claim to have done the hardest route and not expect it to get downgraded pretty quickly! If you are confident in your ability to assess the risk, you are free to move as far left or right of the bolts as you like: climbing is an individual experience. From a coaching perspective though someone is paying for information on how to make climbing easier, how to become a better climber and reach their full potential. We find that helping them improve their navigational abilities is essential.

Historical context to Navigation

People often find it easier to understand our approach when given some historical context of the development of the sport. From hill walking to mountaineering to rock climbing and bouldering.

When walking uphill we tend to take smaller or shorter strides as the terrain steepens. We may also zig zag to reduce the incline and reduce physical effort. We will literally navigate our way around any steeper difficult sections. Mountaineers will be drawn to steeper harder sections seeking out more adventure, wondering if the summit can be reached via this harder steeper approach. Mountains can of course offer many different routes and challenges, some of which maybe offering too great a risk without the ability to climb sections of technical cliff faces and ridges. Early mountaineering routes would avoid these features, as without the necessary skill and equipment they were not yet possible.

As mountaineering routes became more technical, taking on steeper more challenging terrain, it became necessary for mountaineers to be more skilled at climbing rock faces. This led to mountain climbers practising these skills on outcrops and cliffs in preparation for climbing in the alps and the greater ranges beyond Europe. This is how traditional climbing was born. Sport climbing followed and then of course the obvious evolution to bouldering -practising hard moves close to the ground as a way of improving performance on roped climbs. These facets of mountaineering are now considered disciplines in their own right. Looking back at each can help in the understanding of how our approach to climbing has been shaped.

Some boulderers will never tie onto a rope. Some rock climbers will never climb a mountain. The thing that they all have in common is that they all fundamentally begin with at first avoiding the most difficult challenges and then gradually seeking out those more difficult climbs. They all also involve navigation but with each one in turn the navigation becomes more subtle nuanced and therefore easier to overlook.

Summary

Navigating the terrain that we move on is the main purpose of all mountaineering disciplines. With a greater number of climbers bouldering (deliberately seeking out hard moves) and/or mainly climbing indoors where route-finding skills cannot be developed or practised, we see teaching climbers how to navigate the rockface and find the easiest safe way as the task of outdoor climbing coaches.

Video

To accompany this article, please watch the Navigation for Rock Climbing-video on the Rock & Sun YouTube channel.

This navigation tool for rock climbing has been developed by Rock and Sun (Trevor Massiah, MCI & Desiree Massiah-Verbeek, RCI) and was published in The Professional Mountaineer, March 2025.