The Art of Redpointing

The Art of Redpointing

Climbing magazines, climbing videos on YouTube and climbers’ posts on social media are predominantly focused on redpoint ascents. The hardest routes in the world are redpoints, such as “La Dura Dura” (9B+/5.15c) sent by Adam Ondra as well as Chris Sharma in 2013, and “Silence” the first route of its grade (9C/5.15d) sent by Adam Ondra in 2017.

Redpointing is crucial to develop as a climber. It raises your overall climbing standard and allows you to climb much harder than when onsighting. This blog exlains how redpointing provides opportunities for learning and growth. It also describes what can be considered an effective redpointing process.

What is Redpointing?

Redpointing is lead climbing a route without falling or resting on the rope, having previously tried and failed to climb the route cleanly, either on toprope or lead. Before the successful redpoint, this process is also referred to as ‘projecting’, or trying a project.

The term redpointing originates from the mid 1970s, when German climber Kurt Albert recognised the potential of free climbing (as opposed to ‘aid climbing’) and started to free climb in his local area, the Frankenjura. While he was attempting to climb the route free, he would paint a red X on the rock near the pitons when he no longer needed these as aids, as handholds or footholds. Once he was able to climb the whole route without using any of the pitons, he would paint a red dot at the base of the route, to mark that he had achieved his goal of free climbing the route. This rot-punkt was translated to red-pointing. The concept of redpointing (as in: free climbing, not the idea of painting red dots on the rock) became very popular in the 1980s and 1990s with the increase of sport climbing worldwide.

Some climbers never redpoint

Redpointing has become the most popular way to sport climb as people recognize its usefulness in raising their standards. That said, we work with hundreds of climbers a year and quite a few of them say they have never had a project, and never enter into a redpointing process. Instead, they choose to mainly focus on onsighting, which can be great (see our blog “How to improve your Onsight grade”), but in our opinion onsighting will inevitably result in the need for redpointing. If climbers pick the right challenge for themselves when aiming to onsight a route, then they will at some point fail their onsight. Rather than walking away and trying another route, this should be seen as a crucial opportunity for learning and improvement.

There are some good reasons (or excuses) to not enter into red-pointing. Climbers associate it with a fear of falling (and they will generally make more ‘air miles’ while redpointing than when onsighting). Redpointing can also be associated with a sense of failing, as by definition you are not getting to the top in one go. Also, redpointing can be mentally, emotionally and physically exhausting. If not careful, it may result in disappointment, frustration, dissatisfaction and/or tears. Many climbers therefore prefer onsighting: they would be less likely to fall (i.e. they experience less or no fear), and they get to the top in one go (i.e. they get the immediate reward).

So although onsighting is fun and probably the best thing to do when on a short climbing break in an area where you haven’t climbed much before, there are a lot of climbers out there, who just always try to onsight, and don’t ever allow themselves to redpoint – even if it is just turning a failed onsight into success by climbing it a 2nd or 3rd time.

The short-term gains and rewards of only ever onsighting don’t outweigh the long-term losses. What I mean is that by only onsighting climbers are not allowing themselves to get the most out of their climbing potential. They haven’t explored their limits. They are staying within the boundary of their ‘onsight-grade’.

Why red point?

Redpointing should be part of everyone’s training. It is not something that is only for ‘good’ climbers. Every climber, beginner or advanced, can use redpointing to push their limits and increase their standards.

I differentiate here between a quick redpoint (about 3 attempts), and a longer redpoint process where you have chosen a proper project.

A quick redpoint should at least be done occasionally, after a failed onsight. Trying the route a second or third time, means you give yourself the opportunity to turn ‘failure’ into ‘success’. You will learn from whatever mistake you made on your first attempt; maybe you went the wrong way, maybe you ended up wrong-handed, maybe you missed a rest. Entering into a redpointing process, and spending more time on finding the correct route, or figuring out a specific crux sequence, means you will improve your route-finding skills as well as your problem-solving skills.

Redpointing a route that is significantly harder than anything you have climbed before comes with even more advantages. When I first try a route like this, thoughts enter my head such as ‘this is way out of my league’, ‘this is just impossible’, ‘I will never be able to climb this’, ‘this route is Chinese to me – I don’t understand any of it’. It is a very fulfilling process to slowly, step by step figure out how to climb it and turning the impossible into the possible.

When sending your project, it is very well possible that you won’t just do it by the skin of their teeth; it may well feel relatively easy! This is because during all those climbing sessions you got to know the route in a much more intimate way, and you figured out how to climb this route in the very best way, knowing that you need to get everything right in order for you to be able to climb this. You are increasing your movement repertoire (i.e. your personal ‘dictionary of moves’) and by doing these same moves over and over again, you are perfecting them and building muscle memory.

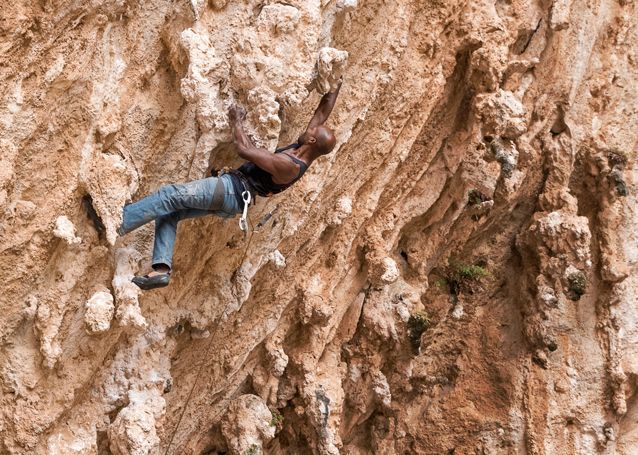

When you are sending the route it may feel like (and/or look like to other people at the crag) a dance up the rock. You are climbing the route with style, with poise, in a state of flow. Even though the route was too hard to start with, and didn’t allow you to get into a rhythm, once your technical ability and knowledge of the route matches the challenge of your project, you are likely to experience the well sought-after flow experience.

Entering into a long and demanding and challenging process also provides the opportunity to deal with failure. If you’re not falling, you’re not trying hard enough. If you want to get close to the best you can be, then climbing is largely about failure. You will fail more often than you succeed and you may as well (learn to) enjoy this process. Redpointing is a good way to get used to collecting more failures than successes. Plus, that one-time success makes up for all the failed attempts before it.

It also helps to redefine failure and success; failure is not having tried your best and/or not enjoyed your day, and success is having tried your best and/or being happy. Climbing is much more than touching the chains. Spending time outside, climbing and trying hard, falling off, solving the puzzle bit by bit (or even seemingly making no progress at all), sharing beta, and hanging out with your mates all make for positive climbing experiences.

An effective redpointing process

- It all starts with picking the right route. To ensure you set yourself the right challenge it would be a minimum of two grades above your usual onsight grade. Another thing to consider is the location of your project; it is more convenient to have a project close to home or in an area that you can go to at least a few times a year. When the gaps in between ‘tries’ are too big, you are more likely to lose progress made in the previous session. Thirdly, a route with good conditions would be ideal; for instance in the Costa Blanca it is nicer to have a project with afternoon shade than one with morning shade, because by the time you have warmed up your project could be in the sun (climbing in the sun is not conducive for good results most of the year in Spain). Last but certainly not least, pick a route that grabs your attention. An outstanding line or feature. A route that you really want to climb. A route that you don’t mind doing over and over, because you just love the moves on it.

- Start climbing the route from bolt to bolt. If you can’t do a section in between bolts – or simply if you want to speed up the process and not waste too much energy, use a stick clip to clip the next bolt. In most cases, you can stick clip the whole route. Sometimes this may not be possible if the route goes over a bulge, or if a bolt is awkwardly placed and doesn’t allow the stick clip to get in. You can also use a stiff clip or panic draw to make it easier to clip the next bolt.

- Now you have the rope up, toproping the route can be useful. You need to be careful though not to overdo it. You will need to understand the clipping positions and how exposed the gaps between the bolts may feel when on lead.

- Lead the route bolt to bolt. Try to solve the puzzle section by section. When clipping the bolt, don’t say tight and wait for your belayer to take in. Instead, clip and let go (providing the fall is safe of course). This conserves energy rather than waiting for the rope to be taken in, and it is a useful falling practice at the same time.

- While bolt-to-bolting, avoid the temptation to do the easier sections too quickly, because in the end all energy saved lower down will help you in the crux. Work the route and its rests until it feels absolutely right for your body/physique, until you’ve ironed out all inefficient moves.

- Make sure to also repeat the section from the last bolt to the anchor! It is a common mistake people make to bolt-to-bolt every section many times, but then only do the finish once or twice, because they’re at the anchor now and think the bolt-to-bolting is finished. It is important to have those top moves wired; when bolt-to-bolting these moves may feel easy, but that could feel different when doing the route in a oner and arriving there completely pumped. You don’t want to fall off after all the cruxes and after pretty much having climbed the whole route, simply because you didn’t have the top moves wired.

- Before it is time to consider trying the route, proceed to combining sections until you can climb the route from ground to the first rest, from the first rest to the second rest, etc, until the clipping of the anchor. When in the rests, which are usually near a clipping position, ‘practice the rest’ but then have a proper rest on the rope. Don’t just rest on the rock as you would be if you were in your redpoint attempt. Be disciplined, even when it is starting to feel easier.

- A very important next step, and at the same time a good gauge of whether you are ready to start trying to send the route, is visualisation. Visualise yourself climbing the whole route, noticing every foot- and handhold, every rest and clipping position, every dynamic move, even where you will calm yourself back down by taking deep breaths. By the time you can visualise the whole route, you are very close to a clean ascent. Some people integrate visualisation with their meditation routine, or visualise just before falling asleep. It is also smart to visualise while you are getting ready to climb the route, and to continue visualisation while resting on the route. Visualisation is widely recognised as a very powerful tool in sports.

Climbing is a creative puzzle solving process that may require patience. A redpoint may take weeks or years. Adam Ondra for instance went to Flatanger 7 times in 2016 and 2017 for an average time of two or three weeks, and he reckons it took several hundreds of attempts before he climbed “Silence” (9C/5.15d).

A few years ago I coached Cheryl on her project, a beautiful >30m 6C in Thailand called ‘Family Affair’. We were both fully committed to her sending this route and the whole process was unforgettable for both of us. On every attempt, it was as if the whole world stopped, and it was just us there, silent, as if we were communicating through the rope. When she sent it, she said something that I since then like to remind myself and others of: She is a professional violinist and described the comparison of redpointing with studying a piece of music. When she first receives the music on paper it just looks like a jumble of notes, it looks impossible. Then bit by bit, line by line she starts to play the notes. Then she tries to play all the lines on the page. And she goes to the next page, trying to play every note. Until, after many hours of practice she is able to play the whole piece from start to finish. And, she said: and thát is when it starts! Because then you can play the piece again, but play it with feeling, play it the way it was meant by the composer. Not just as a succession of notes, but as a story. I love that analogy and feel that the same goes for climbing: there is a difference in climbing from hold to hold, and climbing as a dance up the rock.

Conclusion

Redpointing should be part of every climber’s training. It allows you to grow as a climber. It increases your movement repertoire, it improves your climbing grade, and it provides the opportunity to redefine ‘success’ and ‘failure’.

To those climbers who categorically avoid redpointing: it can easily be argued that red-pointing is easier than onsighting, both mentally and physically. There is the advantage of knowledge of the route. As opposed to onsighting, you know what’s about to come, you know the moves and how likely it is you are able to do them. You know that there are rests on the route and where and how good they are. You know where you are likely to fall off and what that fall will be like. Also, while practicing the route and working out the most efficient sequence in between every bolt, you’re only climbing from bolt to bolt and can then rest on the rope, to do the next section completely fresh, as opposed to onsighting where the pump may be building up. End the excuses: allow yourself to get the best out of yourself by (at least occasionally) engaging into a redpoint process.

If you would like to improve your climbing potential and learn how to redpoint you may want to consider joining Rock & Sun’s Performance Coaching Course. Most climbers come away from that week’s course having climbed two grades harder than they have done before, thanks to the combination of technique coaching and engaging in a redpoint process.

(written by Desiree Verbeek)